Should Globalisation Get Pulled Over for Speeding?

September 9, 2016 § 1 Comment

BY TIM MARTIN AND NATASHA MARTIN

If you’re reading this, your life is probably better because of globalization.

Consider the device on which you are reading this post. For the first time in human history, most of us on this planet are touched by people, ideas, work and products from everywhere. The miracle of cheap airfare takes us to the remotest corners of the earth. We know more and are more interested about people who are different from us.

For both of us – father and daughter – our careers, friendships and hopes depend on an open world. A globalized world. Both of us still believe this is where our future opportunities will be found. We think this is true for everyone on the planet.

We are worried that this system is crashing.

Globalization is crashing into old ideas and ugly prejudices. More than that, it is crashing into politicians without the creativity to govern the new transnational spaces where globalization happens.

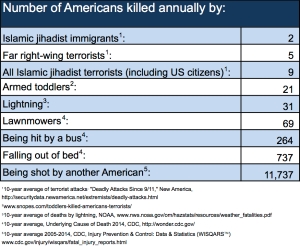

Don’t get us wrong. The problems are real, too. The Great Recession of 2008 was thanks to over clever avarice of unregulated financiers. BREXIT, sold with false information and emotional cheap shots, is a now reality. The country that dominated the planet for centuries lost its patience for a few decades of regional cooperation. Seriously? The World War of Terror has ruined millions of lives and is invading the western psyche (in case you are worried about being a victim of terror, please note that a total of 32,675 Americans died in motor vehicle crashes in 2014).

These characters bidding to shape our future, like Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Geert Wilders and Marine La Penn want to drive ships of state their eyes firmly fixed on the rear view mirror. Their ideas come from the bottom of the brain stem where the fight or flight instinct lives. To make things worse, today’s evil supervillain, the self-appointed Caliph al Baghdadi and his so-called Islamic state are trying and succeeding to scare us out of our wits.

If they win, walls are going up. Opportunities that you may take for granted – like global backpacking and international consulting – these may start to disappear.

Globally, divisions the size of mountain ranges are rising between those who gain from globalization and those that are left behind – or hurt. But globalization shouldn’t and needn’t be a zero sum game.

We need globalisation to move at a speed we can understand and talk about. We think that it is time to talk about the attitudes we need to protect the promise of globalization and its potential to build a better future for everyone from freelance programmers to prairie farmers to Himalayan Sherpas.

In our next post we will talk about these attitudes: putting our democracies to work; better accountability for global business; calling out racism and religious intolerance and; giving peace a chance.

4 Foreign Policy Debates Canada Needs before the Next Election: ISIS, Palestine, First Nations and Canadian Investment Abroad

March 1, 2015 § Leave a comment

In his nine years as our leader, Prime Minister Harper has transformed Canadian foreign policy. These eventful years contain three combat missions, a Middle East policy sharply to the right of the international mainstream and free trade deals or negotiations from Honduras to Ukraine. Whether you agree or not, Stephen Harper has made a deep historic impact on Canada’s place in the world. Our next election will determine if we deepen this direction, or set a different international course for Canada.

These are the four topics I want to hear about before I vote. Please comment with what you think.

What else can we do about the Islamic State: A Canadian general told me in 2010 that killing more Taliban would not solve Afghanistan’s problem. The same goes for the Islamic State. We are at the beginning of a long campaign in a long war that does not have a military solution. The solution is for Syrians and Iraqis to responsibly and democratically govern themselves. Seeds of democracy can be planted in the midst of conflict. Training the next generation of political leaders in democratic practice will help them be successful and have positive views of Canada. Cross-border training in municipal governance would speed post-conflict recovery. University classes for refugees preserves human capital and keeps hope in the future alive. We could go big, especially on human rights and help build case files for human rights prosecutions when that time comes. Canada is doing a small amount in these areas, but nowhere near what the military mission costs. Leaders should have a long term civ-mil strategy and tell us what it is.

The State of Palestine: The two state solution for Middle East peace needs another state. We have the State of Israel. We don’t have the State of Palestine – yet. Most Canadians probably don’t realise that almost two thirds of UN members representing most of the world’s population already recognise the State of Palestine. Sweden did it last October.

The Oslo agreements are twenty years old. I don’t think it’s smart to keep expecting negotiations between Palestine and Israel to produce a workable deal. Why not recognize the Palestinian State now and work with others to help it progressively assume its security, democratic and environmental duties over its territory and people? The next Canadian government will need a policy on this, and we deserve a debate about it.

Global Indigenous Rights: First Nations have lived in harmony with their environment for countless generations. Our country has a lot to learn about respecting First Nations rights in this land. Not only the rights granted by the Crown, but also those set out for all Indigenous Peoples by the UN. The fact that Canada is before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on the tragedy of missing and murdered aboriginal women should compel serious action. Canada is one of the few countries that voted against the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, but then we turned around and endorsed it in 2010. It’s a confusing picture. At the same time as (I hope) we move urgently on Indigenous rights in Canada, I think that we deserve a debate on how Canada’s foreign and investment policy can help protect the rights of all Indigenous People across the world.

Investment and Human Rights: After 24 Sussex Drive, the address of the most powerful source of Canadian international influence is 130 King Street West. The Toronto Stock Exchange is a huge source of capital for the global mining and energy sector and deeply affects environments, economies and societies around the world. There is polarized debate about whether this investment is creating growth and opportunity, or inequality and conflict. If you trade in New York, you have to report your use of conflict minerals, but not in Toronto. I want to hear what the leaders say about their policies for Canadian mining and energy investment abroad and how the Canadian capital market can best support peace and development the world.

What debates do you want to see?

Final Post in the Series Six Things I Learned after Thirty Years in the Foreign Service: People Remember you more by how you say Goodbye than how you said Hello

November 14, 2014 § 1 Comment

We are so often told – and it is true – that you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. It is equally true that last impressions are those that endure in the memory of others when we are absent. In our rotational lives as diplomats, the way we take our leave is how we truly convey that we will continue to care about our friends, even after we have left.

In 1996 I was preparing to leave from my second posting which was in Addis Ababa. It was an exhilarating and exhausting assignment. As a junior diplomat I was responsible for Canada’s political, trade and consular affairs in Ethiopia, Sudan, Eritrea and Djibouti. It had been a rewarding three years, but it was time for me and my family to start a new chapter. I had been diligent in my professional and official work. However, it wasn’t until I was in the airport ready to depart the country that I was able to recognize an error I committed on the human side. A man I had worked with saw me at the airport and asked me a question that I was unable to properly answer.

“Why didn’t you say good-bye to me?”

It hit me like a ton of bricks. I had insulted him by failing to pay him the courtesy of a respectful farewell. In my mind, I had been a responsible bureaucrat, focusing on the work I did for my country instead of myself as an individual. I thought it was better to stick to my work right to the end and avoid the expense and effort of a good-bye reception. My behaviour sent the signal that I placed a low value on my relationships.

The final thing I learned after 30 years is that people remember you more by how you said goodbye, than how you said hello.

Peace, Security and the Global Extractive Sector

September 17, 2014 § 1 Comment

New ethical supply chains that connect small scale miners in conflict affected countries to smart phone consumers and cut out the warlord show that the international system is learning to do a better job of managing the extractive sector, but it has been a long process. The President of Resolve, Stephen D’Esposito, and I have just published an article on Resolve’s work on the supply chain frontier entitled Conflict Minerals, Ethical Supply Chains and Peace in this month’s journal of the Alliance for Peacebuilding, Conflicts of the Future. You can also read about Motorola’s contribution through closed supply chains in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Mike Loch’s article Taking the Conflict out of Conflict Minerals.

Peace, security and the global extractive sector have been increasingly central to Canada’s international policy. Looking back to the 90’s we had the disturbing example of a Canadian company producing oil on the front lines of the Sudanese civil war. Today, it is hard to imagine any major multinational insisting that its commercial interests could trump human rights considerations.

Since that time there have been important milestones in pulling the sector towards better standards of responsibility. In the terrible period of instability in the DRC after the Rwandan genocide, the UN Security Council examined the role of natural resources in conflict for the first time, but without real mechanisms to do anything about it. The Kimberley Process to Ban Conflict Diamonds (which I had the honour to chair in 2004) transformed the global trade in rough diamonds through establishing criminal penalties for any international transactions in uncertified rough diamonds. More recently, the UN has adopted guidelines for business and human rights. In 2012 the Securities and Exchange Commission required listed companies to report on their use of conflict sensitive minerals from the DRC region. Last year, the OECD has put forward guidelines on conflict free due diligence for sensitive minerals, guidelines which are not restricted to the Central Africa region and have particular relevance for Latin America. These milestones are a credit to the work of leaders in all sectors – government, industry and civil society.

More than ever, resource diplomacy needs to accompany growth of the sector. This means voluntary, multi-sector interventions across the supply chain to prevent conflict and harness the social development potential of the extractive sector.

I invite you to read our articles and very much look forward to your comments.

Don’t let your Ego and your Job Fall in Love

April 28, 2014 § 4 Comments

Diplomacy was born in the rarefied upper reaches of aristocracy when monarchs governed through their courts and when power and aristocratic station were two names for the same thing.

Canada is surely among the most egalitarian societies on the planet. Moreover, our culture has a strong current of anti-elitism running through it. But when we enter into the diplomatic and high-level international policy profession, our job often becomes synonymous with entry into the upper strata of the elite in our host countries. There is tension and hazard here.

Whether you are a diplomat or a country manager for a multinational, the natural habitat is the upper crust. This seductive phenomenon is more acute in societies marked by inequality and class division. Let’s face it, people are uncomfortable mingling across social divisions. Mingling upwards takes people out of their comfort zone and makes some worry about the risk of rejection. It’s hard for most people to reciprocate the classy and fancy hospitality that high level diplomats and international executives are expected to offer. A real effort is needed to make friends across social divisions.

International policy professionals need to be aware of this peculiar workplace hazard. There is a risk that your ego can inflate past your personal attributes in order to meet the level of flattery that your powerful position attracts.

In my experience, this ego expansion is obvious to our compatriots. It annoys them. Like an open fly, nobody will tell you if they see it, except your spouse or best friend – after it is too late. So we better be very self-aware. However, we also need to be skilled in multiple modes of behaviour. Our jobs require that we conduct ourselves with dignity, confidence and comfort in high level, formal and public occasions. This is being a good steward of the prestige of our office. Then we need to return safely to the ground. Good diplomats are authentic people at the same time.

Trust, if You can Earn It, is our most Precious Asset (Six Things part 3)

March 31, 2014 § Leave a comment

The stereotype image of diplomacy is cold and calculating men in suits projecting national interests in the lofty heights of global power. I think this is wrong. Like all meaningful human endeavor, diplomacy requires personal relationships between people and we are emotional beings. Trust is our most precious asset and trust is about feelings and personal conduct. Nothing good can be achieved without it.

When we opened Canada’s Representative Office to the Palestinian Authority in Ramallah, Palestine in 1998, there was an overarching economic priority. This was our promise that, following the signature of the 1997 Canada Israel Free Trade Agreement, Canada would secure an agreement with the Palestinians that provided them the same market access benefits. Prior to the opening of our Representative Office in Ramallah in 1998 we tried and tried but couldn’t close the deal. We were under pressure to conclude the agreement in a hurry. This was because the plan was to combine inauguration of the office with a signature of the trade deal.

We wondered: “What could the problem be? This is a good deal.” Then out of the blue, the Palestinians gave us the thumbs up.

In the corridor I asked a young Palestinian negotiator: “What happened?”

She told me: “We met after the negotiations and we talked about your team, and then we decided that you understood our aspirations. After that, we decided that we could make an agreement with you.”

Ultimately, the issue was trust – trust that we would not exploit their vulnerabilities and that we personally cared about the success of the fledgling Palestinian government. Of course, this is not necessarily the case for all trade negotiations. But when there are asymmetric power relations, trust among the players is an essential underpinning for lasting agreements.

Trust is difficult to define, and represents a very high order of human relationship. In my experience it needs direct and repeated human contact, in multiple settings over time. Meetings and memos are inadequate. Sharing a meal in the home is an ancient practice for building trust that enjoys universal recognition and for which there is no substitute.

In our work we often talk about people as “contacts” and ascribe high or low value to them. I think it is important to step beyond this reductive approach and consider systematically who are the people with whom we need to have relationships of trust, how to achieve that trust, nurture and build it. Developing this diplomatic asset requires time and sincere emotional investment. We have to give of ourselves for our job.

In the end, a trust based approach to key relationships leads to more rewarding international policy work, and friendships that can last a lifetime.

Be careful, because the world is more dangerous than it used to be…

February 6, 2014 § 9 Comments

It looks like the world is more dangerous for international policy professionals than it used to be. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t think the world is more dangerous for everybody. Nor should we allow alarming events we see on the news make our fears greater than the actual risks we face.

However, I do think that protection from diplomatic immunities and traditional inhibitions to violence against foreigners is down. Especially in global trouble spots. After all, what is diplomatic immunity supposed to mean in a failed or failing state? Not much.

Diplomats need to work in dangerous places. Countries like Canada have global interests and need a global presence. The civilian work Canada did in Kandahar shows that the Canadian public servants can deliver crucial civilian programs in war zones, especially when it is done in partnership with the Canadian Forces.

But why is there so much rage out there?

I think that there are some powerful psychological drivers of violence at work here. We don’t talk about it much. In a complex international equation, perceived insult leads to humiliation, which generates feelings of rage. This reduces cultural inhibitions to violence.

It gets dangerous when malign leaders exploit grievances against international actors in order to orchestrate violence against foreigners.

I remember April first, 2011 when Florida Pastor Terry Jones burned a Koran. This insult unleashed protests in Afghanistan that were hijacked for violent purposes. There were fatalities and property destruction in Kandahar, and also the tragic killing of seven UN workers in Mazar al Sharif.

Two observations. We know reckless acts like burning a Koran in Florida can have fatal impact on the other side of the world. So let’s keep alive the dialogue about the trade offs between freedom of speech, hate and incitement. We need to do so in a positive spirit of inclusion and responsibility. It would be great to have this conversation outside the crucible of crisis.

Secondly, there is no room for a casual attitude about security. When an officer of an organization is the victim of insecurity, the objective of his whole effort is a victim, too. Lapses in the personal security of individuals can lead to catastrophic policy failures at the level of an organization. International professionals need to take their safety seriously, and organizations need to ensure they have the tools, resources and intelligence to do so.

Is your work getting more dangerous?

Looking forward to your comments.

Tim