Should Globalisation Get Pulled Over for Speeding?

September 9, 2016 § 1 Comment

BY TIM MARTIN AND NATASHA MARTIN

If you’re reading this, your life is probably better because of globalization.

Consider the device on which you are reading this post. For the first time in human history, most of us on this planet are touched by people, ideas, work and products from everywhere. The miracle of cheap airfare takes us to the remotest corners of the earth. We know more and are more interested about people who are different from us.

For both of us – father and daughter – our careers, friendships and hopes depend on an open world. A globalized world. Both of us still believe this is where our future opportunities will be found. We think this is true for everyone on the planet.

We are worried that this system is crashing.

Globalization is crashing into old ideas and ugly prejudices. More than that, it is crashing into politicians without the creativity to govern the new transnational spaces where globalization happens.

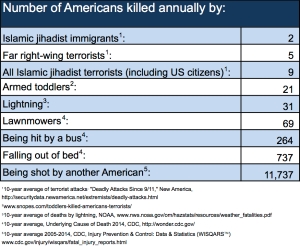

Don’t get us wrong. The problems are real, too. The Great Recession of 2008 was thanks to over clever avarice of unregulated financiers. BREXIT, sold with false information and emotional cheap shots, is a now reality. The country that dominated the planet for centuries lost its patience for a few decades of regional cooperation. Seriously? The World War of Terror has ruined millions of lives and is invading the western psyche (in case you are worried about being a victim of terror, please note that a total of 32,675 Americans died in motor vehicle crashes in 2014).

These characters bidding to shape our future, like Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Geert Wilders and Marine La Penn want to drive ships of state their eyes firmly fixed on the rear view mirror. Their ideas come from the bottom of the brain stem where the fight or flight instinct lives. To make things worse, today’s evil supervillain, the self-appointed Caliph al Baghdadi and his so-called Islamic state are trying and succeeding to scare us out of our wits.

If they win, walls are going up. Opportunities that you may take for granted – like global backpacking and international consulting – these may start to disappear.

Globally, divisions the size of mountain ranges are rising between those who gain from globalization and those that are left behind – or hurt. But globalization shouldn’t and needn’t be a zero sum game.

We need globalisation to move at a speed we can understand and talk about. We think that it is time to talk about the attitudes we need to protect the promise of globalization and its potential to build a better future for everyone from freelance programmers to prairie farmers to Himalayan Sherpas.

In our next post we will talk about these attitudes: putting our democracies to work; better accountability for global business; calling out racism and religious intolerance and; giving peace a chance.

4 Foreign Policy Debates Canada Needs before the Next Election: ISIS, Palestine, First Nations and Canadian Investment Abroad

March 1, 2015 § Leave a comment

In his nine years as our leader, Prime Minister Harper has transformed Canadian foreign policy. These eventful years contain three combat missions, a Middle East policy sharply to the right of the international mainstream and free trade deals or negotiations from Honduras to Ukraine. Whether you agree or not, Stephen Harper has made a deep historic impact on Canada’s place in the world. Our next election will determine if we deepen this direction, or set a different international course for Canada.

These are the four topics I want to hear about before I vote. Please comment with what you think.

What else can we do about the Islamic State: A Canadian general told me in 2010 that killing more Taliban would not solve Afghanistan’s problem. The same goes for the Islamic State. We are at the beginning of a long campaign in a long war that does not have a military solution. The solution is for Syrians and Iraqis to responsibly and democratically govern themselves. Seeds of democracy can be planted in the midst of conflict. Training the next generation of political leaders in democratic practice will help them be successful and have positive views of Canada. Cross-border training in municipal governance would speed post-conflict recovery. University classes for refugees preserves human capital and keeps hope in the future alive. We could go big, especially on human rights and help build case files for human rights prosecutions when that time comes. Canada is doing a small amount in these areas, but nowhere near what the military mission costs. Leaders should have a long term civ-mil strategy and tell us what it is.

The State of Palestine: The two state solution for Middle East peace needs another state. We have the State of Israel. We don’t have the State of Palestine – yet. Most Canadians probably don’t realise that almost two thirds of UN members representing most of the world’s population already recognise the State of Palestine. Sweden did it last October.

The Oslo agreements are twenty years old. I don’t think it’s smart to keep expecting negotiations between Palestine and Israel to produce a workable deal. Why not recognize the Palestinian State now and work with others to help it progressively assume its security, democratic and environmental duties over its territory and people? The next Canadian government will need a policy on this, and we deserve a debate about it.

Global Indigenous Rights: First Nations have lived in harmony with their environment for countless generations. Our country has a lot to learn about respecting First Nations rights in this land. Not only the rights granted by the Crown, but also those set out for all Indigenous Peoples by the UN. The fact that Canada is before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on the tragedy of missing and murdered aboriginal women should compel serious action. Canada is one of the few countries that voted against the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007, but then we turned around and endorsed it in 2010. It’s a confusing picture. At the same time as (I hope) we move urgently on Indigenous rights in Canada, I think that we deserve a debate on how Canada’s foreign and investment policy can help protect the rights of all Indigenous People across the world.

Investment and Human Rights: After 24 Sussex Drive, the address of the most powerful source of Canadian international influence is 130 King Street West. The Toronto Stock Exchange is a huge source of capital for the global mining and energy sector and deeply affects environments, economies and societies around the world. There is polarized debate about whether this investment is creating growth and opportunity, or inequality and conflict. If you trade in New York, you have to report your use of conflict minerals, but not in Toronto. I want to hear what the leaders say about their policies for Canadian mining and energy investment abroad and how the Canadian capital market can best support peace and development the world.

What debates do you want to see?

Two Moral Hazards and a Policy Dilemma in Canada’s Fight against the Islamic State

November 24, 2014 § Leave a comment

I support Canada’s participation in the fight against ISIL. The scale of human rights violations and threat to international peace and security posed by the so-called Islamic State fully justify our combat role. I also support our Government’s incremental approach at this early stage of what will be another long war. Our objective, as stated by Prime Minister Harper to Parliament is to “limit the ability of ISIL to engage in full scale military movements and to operate bases in the open.”

There is no end game, yet. But we need one pretty soon.

The failure of the respective Syrian and Iraqi governments to control their territory or responsibly govern their citizens, combined with the scale, territorial advances and momentum of ISIL, tell us that we are in for a major international campaign. Right now, the confidence of the Canadian public in the Canadian Forces is rock solid. For this to remain so, it is important that we recognize and prepare for the moral hazards that a fight of this nature inevitably entails for Canada and our military. Two come to mind.

Civilian Casualties of the Air Campaign: Thankfully, technical briefings by the Canadian Forces show that the Canadian air campaign has not incurred any civilian casualties yet. But it may happen in the future. The moral hazard of innocent civilian casualties can be attenuated by providing fair compensation for victims. How do we plan to do this?

Human Rights Conduct of the Iraqi Armed Forces and Peshmerga: The refrain has been repeated many times that this will not be about Canadian or American combat boots on the ground. The success of the campaign and our reputation will be affected by the conduct of our partners. We saw this with the issue of detainees in Afghanistan where we decided that Canada needed to directly monitor prisoners after they were passed to Afghan custody in order to prevent torture. Human rights violations by our partners would taint our policy and create yet another layer of grievance to complicate future governance. Are we monitoring the human rights behaviour of our regional military partners?

When the military has turned the tide against ISIL, the requirements of stabilization and reconstruction will come into focus. It will be huge and hugely expensive. It wasn’t until years after we had committed ourselves to Afghanistan that we came to understand the true cost and duration required. A duration that spanned electoral cycles. The policy dilemma is when to decide and seek parliamentary approval for the composition and cost of Canada’s whole of government commitment – and whether to make it proportionate to the challenge.

Final Post in the Series Six Things I Learned after Thirty Years in the Foreign Service: People Remember you more by how you say Goodbye than how you said Hello

November 14, 2014 § 1 Comment

We are so often told – and it is true – that you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. It is equally true that last impressions are those that endure in the memory of others when we are absent. In our rotational lives as diplomats, the way we take our leave is how we truly convey that we will continue to care about our friends, even after we have left.

In 1996 I was preparing to leave from my second posting which was in Addis Ababa. It was an exhilarating and exhausting assignment. As a junior diplomat I was responsible for Canada’s political, trade and consular affairs in Ethiopia, Sudan, Eritrea and Djibouti. It had been a rewarding three years, but it was time for me and my family to start a new chapter. I had been diligent in my professional and official work. However, it wasn’t until I was in the airport ready to depart the country that I was able to recognize an error I committed on the human side. A man I had worked with saw me at the airport and asked me a question that I was unable to properly answer.

“Why didn’t you say good-bye to me?”

It hit me like a ton of bricks. I had insulted him by failing to pay him the courtesy of a respectful farewell. In my mind, I had been a responsible bureaucrat, focusing on the work I did for my country instead of myself as an individual. I thought it was better to stick to my work right to the end and avoid the expense and effort of a good-bye reception. My behaviour sent the signal that I placed a low value on my relationships.

The final thing I learned after 30 years is that people remember you more by how you said goodbye, than how you said hello.

Peace, Security and the Global Extractive Sector

September 17, 2014 § 1 Comment

New ethical supply chains that connect small scale miners in conflict affected countries to smart phone consumers and cut out the warlord show that the international system is learning to do a better job of managing the extractive sector, but it has been a long process. The President of Resolve, Stephen D’Esposito, and I have just published an article on Resolve’s work on the supply chain frontier entitled Conflict Minerals, Ethical Supply Chains and Peace in this month’s journal of the Alliance for Peacebuilding, Conflicts of the Future. You can also read about Motorola’s contribution through closed supply chains in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Mike Loch’s article Taking the Conflict out of Conflict Minerals.

Peace, security and the global extractive sector have been increasingly central to Canada’s international policy. Looking back to the 90’s we had the disturbing example of a Canadian company producing oil on the front lines of the Sudanese civil war. Today, it is hard to imagine any major multinational insisting that its commercial interests could trump human rights considerations.

Since that time there have been important milestones in pulling the sector towards better standards of responsibility. In the terrible period of instability in the DRC after the Rwandan genocide, the UN Security Council examined the role of natural resources in conflict for the first time, but without real mechanisms to do anything about it. The Kimberley Process to Ban Conflict Diamonds (which I had the honour to chair in 2004) transformed the global trade in rough diamonds through establishing criminal penalties for any international transactions in uncertified rough diamonds. More recently, the UN has adopted guidelines for business and human rights. In 2012 the Securities and Exchange Commission required listed companies to report on their use of conflict sensitive minerals from the DRC region. Last year, the OECD has put forward guidelines on conflict free due diligence for sensitive minerals, guidelines which are not restricted to the Central Africa region and have particular relevance for Latin America. These milestones are a credit to the work of leaders in all sectors – government, industry and civil society.

More than ever, resource diplomacy needs to accompany growth of the sector. This means voluntary, multi-sector interventions across the supply chain to prevent conflict and harness the social development potential of the extractive sector.

I invite you to read our articles and very much look forward to your comments.

Do the Right Thing – That’s what People will Remember about Canada

September 15, 2014 § Leave a comment

In Argentina, the Canadian Embassy has been a very close friend to the organization Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo. This is a civic organization which was established because of the practice of the last Argentine military dictatorship to disappear people, which happed to some 30,000 Argentines. The Grandmothers organized their work because, among the disappeared, were hundreds of their young grandchildren and pregnant daughters or daughters-in-law, pregnant with their grandchildren to be. They symbolize a powerful human response to inhuman cruelty and are today helping children of the disappeared discover and recover their identity. You may have seen in the news that this year the leader of the Grandmothers, Estela Carlotta, finally found her grandson (see BBC report here) who was stolen from his mother in 1978 after she gave birth in a detention centre of the military dictatorship.

One day Rosa Rosenblit, Vice President of the Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo came to see me. She wanted to present a book to the Ambassador of Canada. It was a book that chronicled the international support they received in their struggle for justice. She came to the Canadian Embassy because Canada was the first source international support they received. Just as I was puffing myself up to acknowledge and explain Canada’s rich foreign policy tradition in the advancement of human rights, Rosa went on to say that women from a church in Toronto had taken up a collection to send the Grandmothers money and this was the first action of international solidarity to help them. The Canadians were the first foreign friends to do the right thing for the disappeared grandchildren and this will never be forgotten.

We all remember that the Canadian discussion of detainees in Afghanistan has been a matter of bitter controversy. It was a debate about doing the right thing. As you may know, the responsibilities of the Canadian team of civilians in Kandahar included detainee monitoring. This is an unusual diplomatic activity, although routine on the consular side with respect to visiting Canadians in jail abroad. Our work in Kandahar was specialized and involved frequent structured meetings with Afghans detained by Canadian forces and then transferred to Afghan prisons. The monitoring continued until the detainees were sentenced or released and continued after we completed the Kandahar combat and civilian missions (see here).

As we were completing our mission in Kandahar in the run-up to July 2011, I made calls on our Kandahari partners to ask them what they would remember as the Canadian legacy in their province. Some said that they would remember that Canada held the line against the fierce Taliban surprise offensive in 2005 and 2006. Some mentioned the training of police and soldiers. Others spoke about the building of schools and help for Kandahar University or university or irrigation for farmers. Many were amazed that a faraway country would send and sacrifice their young men and women to help Kandaharis. There is no question that Canada has won a prominent place in the history and hearts of the people of Kandahar and I am proud to have been part of that effort. It was one in which Canada was put to the test at the epicenter of the first great geopolitical crisis of the 21st century.

But the most amazing comment that I heard from several people was about our detainee monitoring. We never publicized it actively, although it was included in reports to parliament. But it seemed that everyone in Kandahar knew. Apparently it was discussed on their radio stations. Most people knew someone by first, second or third hand who had been in jail. They were struck and amazed that Canada cared about the rights and dignity of its enemies. Moreover, we demonstrated this not by slogans, but by our conduct. For this, too, Canada will be remembered for doing the right thing.

Six Things part Four: Democracy, Governance and Courage in Afghanistan

June 13, 2014 § Leave a comment

Tomorrow Afghans are voting – in a second round – for the President to succeed Hamid Karzai. I think all of us who care about Afghanistan and democracy should thank candidates Abdullah Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani for their courage and commitment to their country.

I remember an American general officer telling me “We can’t solve this problem by killing more Taliban.” Ultimately, it was understood that the military work was meant to enable the priorities of formal and legitimate Afghan civilian governance to reach the people. It’s hard, but best, when security and governance arrive simultaneously to replace the predators.

State abandonment, or weak, corrupt and illegitimate government enables, and even invites, insurgency. This makes civilian governance dangerous in the extreme for those who enter the arena of democracy in a country in conflict.

Many of those brave Afghans with whom Canada worked in Kandahar made the ultimate sacrifice for governance. The Chief of the Kandahar Police Khan Mohamed Mujahaddin was killed on April 14, 2011. The Mayor of Kandahar City, Ghulam Haider Hamidi was killed July 27, 2011. Faizluddin Agha, District Governor of Panjwa’i, which was the primary focus of the military effort at the time of our departure, was killed on January 13, 2012; Ahmed Wali Karzai, the Chairman of the Provincial Council, was killed July 20, 2011. Fortunately, the excellent Governor of Kandahar, Dr. Tooryalai Wesa has not been harmed by repeated attacks. Within seven months of the completion of the Canadian military and civilian mission in Kandahar, four of the five most important civilian officials in Kandahar province were assassinated. The Taliban insurgency understood, as did we, that it is all about governance.

In the large scheme of things, these men were killed because basic civil governance is utterly incompatible with the Taliban aspiration of the return of the Islamic Caliphate of Afghanistan. Like Mount Everest where they say the hardest part of the climb is the last vertical hundred meters, state extension to the most disadvantaged and needful zones and people is the most difficult increment of post conflict governance. This has led me to the fifth thing I learned in 30 years as a diplomat: development, peace and security are all about governance – its quality, political culture and geographical extension. This idea has also led me to a shift in my diplomatic perspective. When we have willing partners, it is usually more effective to base our diplomacy on how to help states be successful for their citizens, than to try to criticize and constrain them. We want our friends to be successful.

Don’t let your Ego and your Job Fall in Love

April 28, 2014 § 4 Comments

Diplomacy was born in the rarefied upper reaches of aristocracy when monarchs governed through their courts and when power and aristocratic station were two names for the same thing.

Canada is surely among the most egalitarian societies on the planet. Moreover, our culture has a strong current of anti-elitism running through it. But when we enter into the diplomatic and high-level international policy profession, our job often becomes synonymous with entry into the upper strata of the elite in our host countries. There is tension and hazard here.

Whether you are a diplomat or a country manager for a multinational, the natural habitat is the upper crust. This seductive phenomenon is more acute in societies marked by inequality and class division. Let’s face it, people are uncomfortable mingling across social divisions. Mingling upwards takes people out of their comfort zone and makes some worry about the risk of rejection. It’s hard for most people to reciprocate the classy and fancy hospitality that high level diplomats and international executives are expected to offer. A real effort is needed to make friends across social divisions.

International policy professionals need to be aware of this peculiar workplace hazard. There is a risk that your ego can inflate past your personal attributes in order to meet the level of flattery that your powerful position attracts.

In my experience, this ego expansion is obvious to our compatriots. It annoys them. Like an open fly, nobody will tell you if they see it, except your spouse or best friend – after it is too late. So we better be very self-aware. However, we also need to be skilled in multiple modes of behaviour. Our jobs require that we conduct ourselves with dignity, confidence and comfort in high level, formal and public occasions. This is being a good steward of the prestige of our office. Then we need to return safely to the ground. Good diplomats are authentic people at the same time.

Trust, if You can Earn It, is our most Precious Asset (Six Things part 3)

March 31, 2014 § Leave a comment

The stereotype image of diplomacy is cold and calculating men in suits projecting national interests in the lofty heights of global power. I think this is wrong. Like all meaningful human endeavor, diplomacy requires personal relationships between people and we are emotional beings. Trust is our most precious asset and trust is about feelings and personal conduct. Nothing good can be achieved without it.

When we opened Canada’s Representative Office to the Palestinian Authority in Ramallah, Palestine in 1998, there was an overarching economic priority. This was our promise that, following the signature of the 1997 Canada Israel Free Trade Agreement, Canada would secure an agreement with the Palestinians that provided them the same market access benefits. Prior to the opening of our Representative Office in Ramallah in 1998 we tried and tried but couldn’t close the deal. We were under pressure to conclude the agreement in a hurry. This was because the plan was to combine inauguration of the office with a signature of the trade deal.

We wondered: “What could the problem be? This is a good deal.” Then out of the blue, the Palestinians gave us the thumbs up.

In the corridor I asked a young Palestinian negotiator: “What happened?”

She told me: “We met after the negotiations and we talked about your team, and then we decided that you understood our aspirations. After that, we decided that we could make an agreement with you.”

Ultimately, the issue was trust – trust that we would not exploit their vulnerabilities and that we personally cared about the success of the fledgling Palestinian government. Of course, this is not necessarily the case for all trade negotiations. But when there are asymmetric power relations, trust among the players is an essential underpinning for lasting agreements.

Trust is difficult to define, and represents a very high order of human relationship. In my experience it needs direct and repeated human contact, in multiple settings over time. Meetings and memos are inadequate. Sharing a meal in the home is an ancient practice for building trust that enjoys universal recognition and for which there is no substitute.

In our work we often talk about people as “contacts” and ascribe high or low value to them. I think it is important to step beyond this reductive approach and consider systematically who are the people with whom we need to have relationships of trust, how to achieve that trust, nurture and build it. Developing this diplomatic asset requires time and sincere emotional investment. We have to give of ourselves for our job.

In the end, a trust based approach to key relationships leads to more rewarding international policy work, and friendships that can last a lifetime.

RoCK Thoughts on Canada Leaving Afghanistan

March 20, 2014 § 12 Comments

I was the last Representative of Canada in Kandahar (RoCK), and worked with an outstanding team of Canadian civilian professionals to deliver development, humanitarian assistance, human rights and governance right through to the end of our combat mission in July 2011. This was followed by a non-combat, military training mission that ended yesterday, when the last troops came home.

General Dean Milner was the Commander who came home with the troops. He led the Canadian task force in its last combat rotation in Kandahar, and also brought our training mission to its correct completion and will be remembered by Canadian history as one of our great generals. It’s important that our troops have been properly honoured, but in this post I want to talk about the civilian work we did in Kandahar.

In 2011 when Canada completed its Kandahar military and civilian mission, PM Harper said that Afghanistan is no longer a threat to international peace and security. That remains true. It took a long time, a lot of learning and great sacrifice. But reconstructing the Afghan state after its defeat and disastrous collapse, to where it is no longer an international security liability and can defend itself is no mean feat. Significantly, the international effort brought with it great achievements in the civilian domains of humanitarian conditions, social development, economic prospects, human rights and governance. We can debate around the edges, but the historical fact of progress is plain. What’s more, when Canada found itself at the epicenter of the first geopolitical crisis of the twenty-first century, we performed with courage, proficiency and full depth of commitment.

To recap what happened after 9/11 – within 24 hours, NATO invoked the collective defense clause if it was determined that the attack originated outside the US. As we know, it originated in Afghanistan where Osama Bin Laden planned and executed the World Trade Center atrocity. As a matter of fact, Mohamed Atta, pilot of one of the planes, delivered his last will and testament to Bin Laden at Tarnak Farms, the Al Quaeda stronghold in Kandahar. It did not take long for the United States with its allies to utterly defeat the Taliban government in their homeland, which is Kandahar.

But the very difficult part was reconstruction. And then, this difficulty was compounded in the extreme with the surprising emergence of the determined and elusive Taliban insurgency. However, there is no military solution to the problems of reconstruction and development.

In the distribution by NATO of reconstruction responsibilities across the country, and the establishment of Provincial Reconstruction Teams, Canada received the province of Kandahar. Canada learned fast and adapted to put together a remarkably effective combined military/civilian response to the challenges of our area of operations. You will remember that in 2006 Prime Minister Harper tasked John Manley to prepare recommendations on Canada’s future role in Afghanistan for consideration of Parliament.

In his report, Manley said “The essential questions for Canada are: how do we move from a military role to a civilian one, and how do we oversee a shift in responsibility for Afghanistan’s security from the international community to Afghans themselves?”

The operational response on the civilian side was to create a large integrated team of some 80 civilians composed of brave and skilled professionals from across the federal government. Large scale project funding from CIDA and Foreign Affairs was key to support that effort. The RCMP trained Afghan policemen and policewomen. CIDA delivered schools, irrigation canals, vaccination programs and economic development. Corrections Canada brought the notorious Sarpoza prison up to international standards. Foreign Affairs advanced governance, democracy and monitored human rights in Afghan prisons. My American colleague, Bill Harris, described the Canadian reconstruction model as “wildly successful”. (Let me express here my thanks to our US friends and colleagues for their great partnership and the surge, which came to Southern Afghanistan when we needed it.)

It is utterly clear that the courage, skill and resolve of the Canadian Forces were absolutely a necessary condition for a civilian role. Without minimum conditions of territorial control and security, no development can take place and governance can never be more than tenuous. At the same time, once this minimum threshold is achieved, we discovered that security operations, development and governance can take place simultaneously and be mutually reinforcing.

Perhaps the most interesting innovation was in our own Canadian governance. Canada did away with the traditional departmental stovepipes and barriers between organizations to mobilize the assets of the public service to deliver a whole of government effort and an integrated reconstruction package in an active war zone. This is a great but hidden capability of the Canadian public service.

Somalia, Rwanda, Bosnia, Kosovo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, East Timor, and Afghanistan. The last generation of Canadian diplomacy has also been the story of states that catastrophically crash, catch public opinion by surprise and demand a complex international response. In many ways, Canada’s defense, diplomatic and humanitarian policies have been influenced by the tragedy of state failure.

I remember saying to myself in Kandahar that nobody, and certainly not the long-suffering Afghans, deserve the tragedy, pain, poverty and violence that attends state failure. Ultimately, we learned that it’s all about governance. If there was a civ/mil consensus on the challenge in Afghanistan, this is it. But sadly, when we look around, there are new candidates. Divided countries with predatory or incompetent governments end up in crises they cannot resolve without external intervention.

It’s all about governance because a state needs a certain level of legitimacy to defeat an insurgency.

As we look around, there will be other states that fail, and some we won’t be able to ignore. In the meantime, I believe there are four core questions that international policy professionals should be working on so we are prepared when the time comes.

1. How to establish local governance in the absence of state legitimacy?

2. How to pivot from military counter insurgency to civilian peace building and reconciliation?

3. How to create justice before there is a functioning judicial branch?

4. How to combine the resources of traditional tribal community governance with the establishment of a basic national public service.

But really, Canada has not left Afghanistan. We are where Manley and Parliament wanted us to be. We have completely transitioned to a civilian mission under the leadership of Ambassador Deborah Lyons at the Canadian Embassy in Kabul. Afghans can take responsibility for their own security and a new chapter is unfolding. Bin Ladin’s old Kandahar HQ is now an agricultural research farm, thanks to Canadian civilian efforts.